I recently read a short meditation from Fr. Rohr at the Center for Action and Contemplation. In it he explains the journey of finding our purpose in life. He explains;

"There is much evidence that there are at least two major tasks to human life. The first task is to build a strong container or identity; the second is to find the contents that the container is meant to hold. We all try to do what seems like the task that life first hands us: establishing an identity, a home, relationships, friends, community, security, and building a proper platform for our only life.

But it takes us much longer to discover the 'task within the task,' as I like to call it: what we are really doing when we are doing what we are doing."

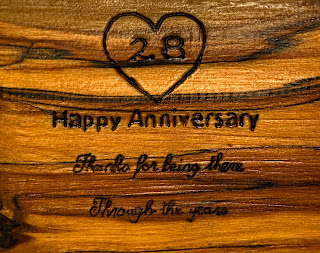

It seems to me that he is saying that it is not only crucial to build a good box, but to also contemplate what we are filling it with.

Spalted birch, tung oil, paste wax finish. Anniversary message written by woodburning on underside of lid.

Friday, February 25, 2011

Wednesday, February 16, 2011

The Ability to Bend

Charles Darwin is often quoted (and some would say, misquoted) to have said, "It is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change."

That came to mind this week as I was trying to fashion a handle for my wooden bucket that is part of a group project posted on the LumberJock website.

Four times I tried to coax a narrow strip of spalted birch into a nice, round half circle; by soaking it overnight, by steam bending, by hot pipe bending - all with the same result. I'd get a few degrees of deflection and snap! I'd be holding two separate pieces in my hand. It was getting discouraging to say the least.

Four times I tried to coax a narrow strip of spalted birch into a nice, round half circle; by soaking it overnight, by steam bending, by hot pipe bending - all with the same result. I'd get a few degrees of deflection and snap! I'd be holding two separate pieces in my hand. It was getting discouraging to say the least.

I decided it just wasn't going to happen, so I changed tactics. Finding a clear, 2 inch diameter section of willow from the trimmings pile under a snowbank outside, I headed for my band saw. Minutes later I had several nice, flat, 3/8 inch strips in my hand. After placing the kettle on the stove, I fashioned a short tube to act as my steam chamber. Ten minutes after the steam started to flow the willow was as compliant as my children are when promised an evening at the movies.

So what made the difference? I'm sure there is a scientific explanation that in some way involves lignin and white rot fungi which would take way too much effort for me to uncover, so I'm happy with the obvious.

The strip of birch didn't want to bend. It liked things just like they were. After all, that's how it was made to be, had always been that way, and would change over its dead body! So with all the resistance it could muster, it balked all my pressures to bend and as a result ended up broken and discarded.

The strip of birch didn't want to bend. It liked things just like they were. After all, that's how it was made to be, had always been that way, and would change over its dead body! So with all the resistance it could muster, it balked all my pressures to bend and as a result ended up broken and discarded.

Oh, to just have the courage to change.

That came to mind this week as I was trying to fashion a handle for my wooden bucket that is part of a group project posted on the LumberJock website.

Four times I tried to coax a narrow strip of spalted birch into a nice, round half circle; by soaking it overnight, by steam bending, by hot pipe bending - all with the same result. I'd get a few degrees of deflection and snap! I'd be holding two separate pieces in my hand. It was getting discouraging to say the least.

Four times I tried to coax a narrow strip of spalted birch into a nice, round half circle; by soaking it overnight, by steam bending, by hot pipe bending - all with the same result. I'd get a few degrees of deflection and snap! I'd be holding two separate pieces in my hand. It was getting discouraging to say the least.I decided it just wasn't going to happen, so I changed tactics. Finding a clear, 2 inch diameter section of willow from the trimmings pile under a snowbank outside, I headed for my band saw. Minutes later I had several nice, flat, 3/8 inch strips in my hand. After placing the kettle on the stove, I fashioned a short tube to act as my steam chamber. Ten minutes after the steam started to flow the willow was as compliant as my children are when promised an evening at the movies.

So what made the difference? I'm sure there is a scientific explanation that in some way involves lignin and white rot fungi which would take way too much effort for me to uncover, so I'm happy with the obvious.

The strip of birch didn't want to bend. It liked things just like they were. After all, that's how it was made to be, had always been that way, and would change over its dead body! So with all the resistance it could muster, it balked all my pressures to bend and as a result ended up broken and discarded.

The strip of birch didn't want to bend. It liked things just like they were. After all, that's how it was made to be, had always been that way, and would change over its dead body! So with all the resistance it could muster, it balked all my pressures to bend and as a result ended up broken and discarded. Oh, to just have the courage to change.

Saturday, February 5, 2011

Finding the Dōgu - the Way of Tools

There is an online article written by Dave Lowry addressing the tools of the traditional Japanese craftsman. In the article was a story of an old hermit woodcutter that died in the 1950's. Among his possessions was found a yellowed slip of paper with the woodcutter's last wishes simply written down. Dave recounts the hermit's desires for his most cherished tool:

There is an online article written by Dave Lowry addressing the tools of the traditional Japanese craftsman. In the article was a story of an old hermit woodcutter that died in the 1950's. Among his possessions was found a yellowed slip of paper with the woodcutter's last wishes simply written down. Dave recounts the hermit's desires for his most cherished tool:"I have called this axe Hige-giri ('Beard-cutter')," read the paper. "I hope, when I die, it will be loved and used by one who truly appreciates its qualities." The note concluded, "I have nothing in life worth a thing except for this excellent axe. But then again, with an axe such as this, how much in life does one need?"

There is a strong connection in the traditional Japanese culture between the shokunin, or master craftsman, his tools, and his work. And through his work he is strongly connected with his community. Toshio Ōdate describes it this way:

There is a strong connection in the traditional Japanese culture between the shokunin, or master craftsman, his tools, and his work. And through his work he is strongly connected with his community. Toshio Ōdate describes it this way:"The shokunin has a social obligation to work his best for the general welfare of the people. This obligation is both spiritual and material, in that no matter what it is, if society requires it, the shokunin's responsibility is to fulfill the requirement. The relationship of a shokunin to his tools is therefore very close, for it is through the tools that the work of the shokunin is created. Each of the shokunin's tools is his life and pride." (Introduction, "Japanese Woodworking Tools: Their Tradition, Spirit, and Use" The Taunton Press, 1984)

There is a profound lesson in simplicity, contentment, and humility in considering the life of the shokunin. It is a value sadly lacking in our industrially bred, consumer fed society, and I would suggest we all suffer because of it.

Wednesday, February 2, 2011

Pursuing Beauty in the Shop

The late Saul Bass, an accomplished and recognized graphics designer, said in an interview in 1987:

"Aesthetics are your problem and mine; nobody else's. The fact of the matter is, I want everything that we do, that I do personally, that our office does, to be beautiful. I don't give a damn whether the client understands that that's worth anything, or that the client thinks it's worth anything, or whether it is worth anything; it's worth it to me. It's the way I want to live my life. I want to make beautiful things, even if nobody cares."

I've been "noodling" and "futzing" with a wooden plane I've been building for the past few weeks, and am now searching for an acceptable plane iron for it. It's been a fun project, and it's all part of a wooden bucket blog on the Lumberjocks website. The carvings are my attempt at acanthus leaves, a very common detail in early Greek architecture, traditionally used to symbolize enduring life or immortality. The scrolling form of the acanthus leaf has become a very popular decorative feature in wood carving and one I've been anxious to try, and this was a perfect opportunity to bring something a little extra to an otherwise simple project.

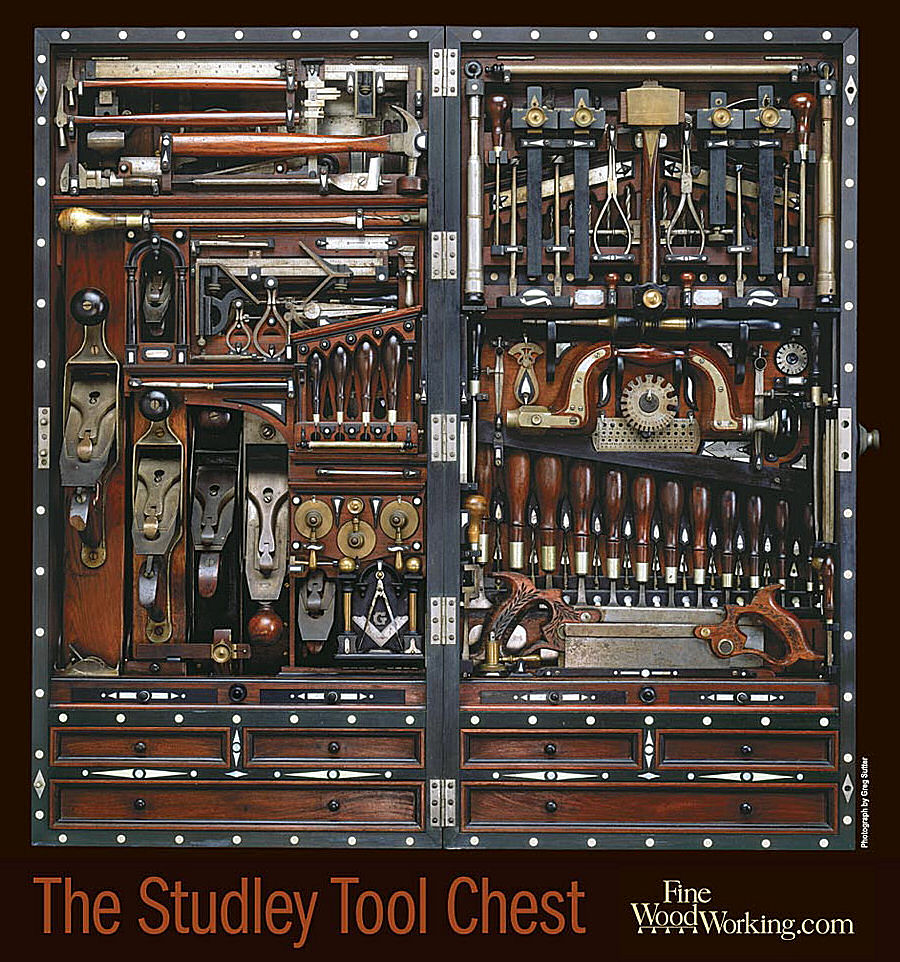

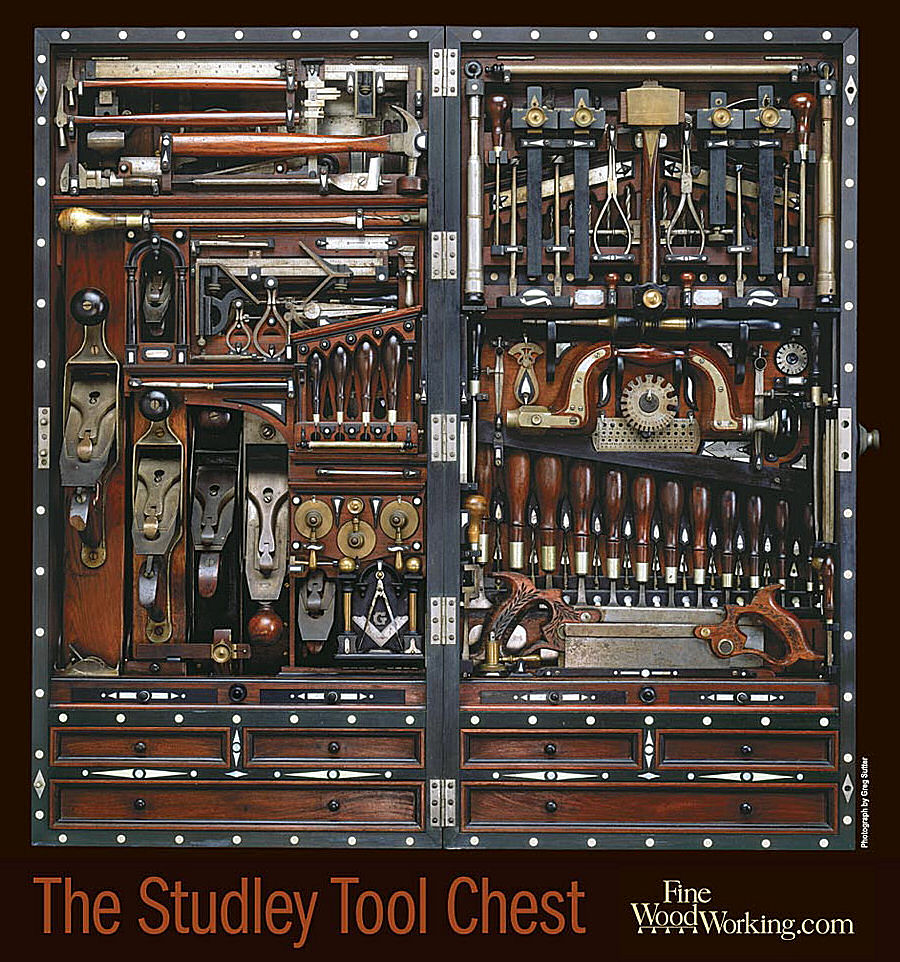

The tradition of decorating hand tools is something that has been sadly lost to our generation but was very common in the earlier centuries. Often the workman's tools as well as his tool chest was considered to be a testament to his craft and proudly displayed as his ability to create beauty in his work. One famous example of this is the amazing tool chest of Henry O. Studley (1838 - 1925), a piano and organ maker that worked for the Poole Piano Company in Boston, Massachusetts that is currently part of the "Tool Chests, Symbol and Servant" display at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington DC. It held an estimated 300 tools and is an incredible display of his pride in fine workmanship and quality. This would have fit well with the philosophy of Bass, as the appreciation of beauty is clearly present, regardless if the client had any appreciation for it or not.

The tradition of decorating hand tools is something that has been sadly lost to our generation but was very common in the earlier centuries. Often the workman's tools as well as his tool chest was considered to be a testament to his craft and proudly displayed as his ability to create beauty in his work. One famous example of this is the amazing tool chest of Henry O. Studley (1838 - 1925), a piano and organ maker that worked for the Poole Piano Company in Boston, Massachusetts that is currently part of the "Tool Chests, Symbol and Servant" display at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington DC. It held an estimated 300 tools and is an incredible display of his pride in fine workmanship and quality. This would have fit well with the philosophy of Bass, as the appreciation of beauty is clearly present, regardless if the client had any appreciation for it or not.

My attempts of individuality through the pursuit of beauty is nothing compared to the caliber of Mr. H. O. Studley, but a little of the pleasure and commitment is still there. And as someone once said,

"Working with a beautiful tool is like dancing with a beautiful woman - it doesn't help you dance any better, but it sure is a lot more fun."

And to me, this new plane will become a beautiful dancer indeed.

"Aesthetics are your problem and mine; nobody else's. The fact of the matter is, I want everything that we do, that I do personally, that our office does, to be beautiful. I don't give a damn whether the client understands that that's worth anything, or that the client thinks it's worth anything, or whether it is worth anything; it's worth it to me. It's the way I want to live my life. I want to make beautiful things, even if nobody cares."

I've been "noodling" and "futzing" with a wooden plane I've been building for the past few weeks, and am now searching for an acceptable plane iron for it. It's been a fun project, and it's all part of a wooden bucket blog on the Lumberjocks website. The carvings are my attempt at acanthus leaves, a very common detail in early Greek architecture, traditionally used to symbolize enduring life or immortality. The scrolling form of the acanthus leaf has become a very popular decorative feature in wood carving and one I've been anxious to try, and this was a perfect opportunity to bring something a little extra to an otherwise simple project.

The tradition of decorating hand tools is something that has been sadly lost to our generation but was very common in the earlier centuries. Often the workman's tools as well as his tool chest was considered to be a testament to his craft and proudly displayed as his ability to create beauty in his work. One famous example of this is the amazing tool chest of Henry O. Studley (1838 - 1925), a piano and organ maker that worked for the Poole Piano Company in Boston, Massachusetts that is currently part of the "Tool Chests, Symbol and Servant" display at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington DC. It held an estimated 300 tools and is an incredible display of his pride in fine workmanship and quality. This would have fit well with the philosophy of Bass, as the appreciation of beauty is clearly present, regardless if the client had any appreciation for it or not.

The tradition of decorating hand tools is something that has been sadly lost to our generation but was very common in the earlier centuries. Often the workman's tools as well as his tool chest was considered to be a testament to his craft and proudly displayed as his ability to create beauty in his work. One famous example of this is the amazing tool chest of Henry O. Studley (1838 - 1925), a piano and organ maker that worked for the Poole Piano Company in Boston, Massachusetts that is currently part of the "Tool Chests, Symbol and Servant" display at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington DC. It held an estimated 300 tools and is an incredible display of his pride in fine workmanship and quality. This would have fit well with the philosophy of Bass, as the appreciation of beauty is clearly present, regardless if the client had any appreciation for it or not. My attempts of individuality through the pursuit of beauty is nothing compared to the caliber of Mr. H. O. Studley, but a little of the pleasure and commitment is still there. And as someone once said,

"Working with a beautiful tool is like dancing with a beautiful woman - it doesn't help you dance any better, but it sure is a lot more fun."

And to me, this new plane will become a beautiful dancer indeed.

Tuesday, February 1, 2011

Projects Outside the Workshop

One of the lingering benefits from our sailing experience has been the appreciation and satisfaction that comes from being self sufficient. Our boat was completely able to operate "off the grid" and many weeks could pass before we would need to find a port to re-provision with supplies or water. We would supplement our supplies with fishing and berries while in remote areas, and simple repairs were done with supplies on hand. Major failures were either "jury rigged" or done without until proper repairs could be made in port. This independent style of living brought a lot of satisfaction in the knowledge that we could look after ourselves.

This desire for self sufficiency continues to impact how I continue to live on land and that feeling of independence is a major part of the satisfaction I enjoy when completing a project. Not everything I need requires a trip to the store - often the materials are readily available and simple - and the supplies we do purchase tend to be more of the basics and less of the processed or finished product. This last weekend was no exception - and the satisfaction just as real as any project I've churned out in the workshop - even though this one came from the kitchen.

My grandmother is reputed to have said that "no-one will ever starve as long as they keep a sack of beans stored in the attic." Whether she actually did keep any stashed away is unknown, but her words ring true. Simple provisions - rice, beans, TVP, flour - can provide the basics for many meals and are easily stored for long periods provided they remain dry. This weekend's project was tackling one of those provisions; one we enjoy keeping stocked in our "attic."

The recipe I use is adapted from Mennonite's Country-Style Recipes by Esther H. Shank (Harold Press, 1987):

8 cups beans, soaked overnight and cooked for 1 hr in same water, drained, reserving liquid

1 lb bacon, cut into small pieces

2 onions, chopped

1 cup brown sugar

3 cups ketchup

1/2 cup molasses

4 Tbsp prepared mustard

4 tsp salt

1 tsp cinnamon

1/2 tsp ground black pepper

Mix well along with 4 cups of the reserved bean liquid, fill pint jars and process in pressure canner 75 min at 10 lbs pressure.

There's just something extremely satisfying with a well stocked shelf filled with jars you've prepared yourself.

Even if it did happen in the kitchen.

This desire for self sufficiency continues to impact how I continue to live on land and that feeling of independence is a major part of the satisfaction I enjoy when completing a project. Not everything I need requires a trip to the store - often the materials are readily available and simple - and the supplies we do purchase tend to be more of the basics and less of the processed or finished product. This last weekend was no exception - and the satisfaction just as real as any project I've churned out in the workshop - even though this one came from the kitchen.

My grandmother is reputed to have said that "no-one will ever starve as long as they keep a sack of beans stored in the attic." Whether she actually did keep any stashed away is unknown, but her words ring true. Simple provisions - rice, beans, TVP, flour - can provide the basics for many meals and are easily stored for long periods provided they remain dry. This weekend's project was tackling one of those provisions; one we enjoy keeping stocked in our "attic."

The recipe I use is adapted from Mennonite's Country-Style Recipes by Esther H. Shank (Harold Press, 1987):

8 cups beans, soaked overnight and cooked for 1 hr in same water, drained, reserving liquid

1 lb bacon, cut into small pieces

2 onions, chopped

1 cup brown sugar

3 cups ketchup

1/2 cup molasses

4 Tbsp prepared mustard

4 tsp salt

1 tsp cinnamon

1/2 tsp ground black pepper

Mix well along with 4 cups of the reserved bean liquid, fill pint jars and process in pressure canner 75 min at 10 lbs pressure.

There's just something extremely satisfying with a well stocked shelf filled with jars you've prepared yourself.

Even if it did happen in the kitchen.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)